Extraction and transformation of ETF Distributions

For many ETF-products there is almost always two versions available: one that distributes and one that accumulates. The accumulating version reinvests distributions from its holdings. The other distributes in regular intervals the accumulated distributables.

Distributables can be generated from holdings paying dividends for example. For distributing ETFs, these funds are accumulated and then distributed at certain dates and intervals.

When setting up a portfolio plan you make a conscious decision against or in favor of distributing ETF-products. Distributions provide a regular source of income from your portfolio without having to sell any assets. Understanding the patterns of each distributing ETF-product can help to determine when and how many distributions you can expect.

Data Availability

Whereas data for holdings of ETF-product is usually very accessible, information about distribution is not. As usual, different ETF-providers offer different amount of information and data in different formats.

Lyxor provides a download on an xls-file. The information is very easy to extract.

iShares delivers the distribution inside a package of information named “overview”. The download return a file ending with .xls. Unfortunately, it is not an xls file, but a very nested xml file. The extraction of information is a bit tricky. If you are interested, please have a look at the code base.

Sadly, XTrackers does not provide an easy option to access distributions data programmatically. The data is freely available on their website, but there is not functionality for a download. Setting up a webscraper or manually typing of the information is out of scope for now.

Data Structure

The purpose of analyzing the distribution data is to answer the following question:

“How much and when do I get money?”

Concerning the “How much do I get?”, every ETF-provider usually provides this information in fund currency. If the currency is not provided, we will assume it is the fund currency.

To determine “When do I get it?”, there need to be considered the three dates defining the timing of distributions:

- Ex Date

- Record Date

- Payment Date

Starting from the Ex-Date, shares trade ex-distributions. Shares bought during this period do not have a right on the upcoming distribution.

The Record Date usually is two business days after the Ex-Date. It is the date when companies determine who owns the shares and has a right to the upcoming distribution.

On Payment Date, you actually receive the money. Naturally, that is the most interesting date.

Concerning the availability of date information, iShares delivers all three dates. Lyxor on the other hand, only provides one date column which is named “ExDate1”. Which is not a major problem as we can derive all 3 dates from 1 date with a few assumptions.

Data Analysis

For any analysis concerning distributions, it is essentiel to get the timing right. This section will start by analyzing data where featuring all three dates. Meaning, only data from iShares is considered.

The definition of the three dates suggests the following order: Ex Date < Record Date < Payment Date

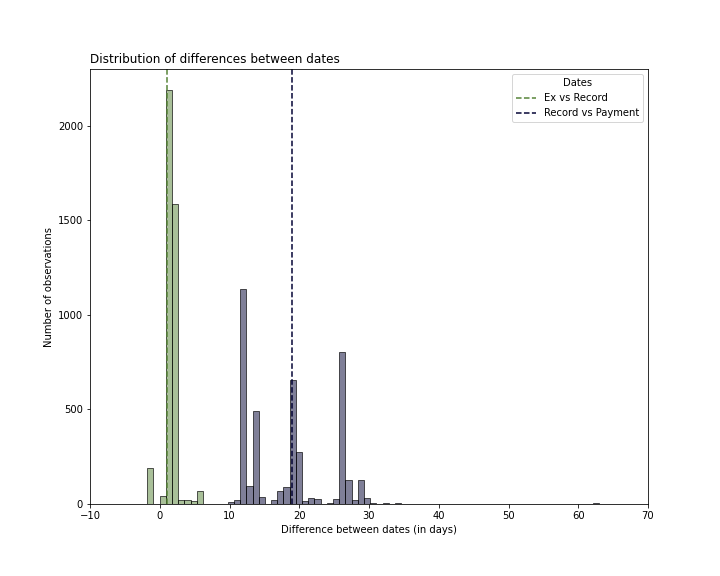

We can observe that the Ex Date and the Record Date actually lie 1 or 2 days apart in most cases. And the payment can be exepected to be executed within 10 to 30 days after the record date.

The maximum and minimum values in the data are extreme and indicate errors. Payment dates about 10 years before the record are nonsense. These are most likely manual input errors and problems with date formats. Continue to the next section for details.

Summary statistis

(Date differences in number of days)

| D Record - Ex | D Payment vs Record | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 4159 | 4159 |

| Mean | 1.22 | 17.72 |

| Min | -320 | -2896 |

| 25% | 1 | 12 |

| 50% | 1 | 19 |

| 75% | 2 | 26 |

| Max | 30 | 338 |

Looking at the actual distribution of the two date differences while excluding extreme outliers produces the following histogram.

The difference between Record and Ex Date are clearly either 1 or 2. While the difference between payment and record date seem to have three humps. This is important information for a subsequent process of data cleaning. It means, that we cannot simply replace erroneous data with values inferred from the whole sample. But rather, we need to look at metrics derived from within each ETF-product.

Data Quality

Concerning the quality of data, we can identify two main issues:

- The order of a date column over different points in time is wrong

- The order of dates (Ex, Record, Payment) within one observation is wrong

The reasons for these types of errors can be numerous. For example, manual input data is very prone to errors. Also, different date formats (namely, MM/DD/YYYY vs DD/MM/YYYY) are trouble for data quality checks. Simple, automated checks can only detect some errors, but have problems with dates like “01/06/2000” vs “06/01/2000”. A machine can only determine which date is correct when comparing across records, i.e. over time.

For data provided in Europe, I assume the following date format to be standard DD/MM/YYYY

The ETF with the ISIN IE0005042456 is a good example for a common error. In line number 86, the Ex date is provided as “06/01/2001”, whereas it should be “01/06/2001”. The error can be detected with several criteria.

- Previous records (03/02/2001) are ahead in time

- The Record Date is more than 3 days ahead the Ex Date

- The Payment Date is more than 60 days ahead the Ex Date

This is actual data provided by iShares.

Data Cleaning

We will clean the data in a two-step process:

- First, correct the order for one date, across observations

- Second, correct the order for one observation, across dates

When a date is wrong, we infer its correct value as a relative distance to other dates. As an assumption, the Ex and Record Dates lie 1 day apart. The Record and payment dates are assumed to have a difference equals to the median difference observed within the current ETF-product.

Summary statistics

Date differences in number of days; clean data

| D Record - Ex | D Payment vs Record | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 4159 | 4159 |

| Mean | 1.51 | 18.39 |

| Min | 0 | 0 |

| 25% | 1 | 12 |

| 50% | 1 | 19 |

| 75% | 2 | 26 |

| Max | 30 | 63 |

In total, the algorithm changed the following number of dates:

- Date Ex: 0

- Date Record: 204

- Date Payment: 5

Whereas the record date was in large parts fixed because the order of Ex-Date and Record-Date was swapped, the changes for the payment dates were more substasntial.

Changes in payment dates

In the column “Dist_Date_Payment”, the causes for the errors are highlighted. You can see that the algortihm is doing a good job in fixing these errors.

| Security_ISIN | Dist_Date_Ex | Dist_Date_Record | Dist_Date_Payment | Dist_Date_Ex_Adj | Dist_Date_Record_Adj | Dist_Date_Payment_Adj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE0008470928 | 2008-01-30 | 2008-02-01 | 2007-02-27 | 2008-01-30 | 2008-02-01 | 2008-02-21 |

| IE0031442068 | 2003-02-26 | 2003-02-28 | 2002-03-17 | 2003-02-26 | 2003-02-28 | 2003-03-19 |

| IE0032895942 | 2007-10-31 | 2007-11-30 | 2007-11-28 | 2007-10-31 | 2007-11-30 | 2007-12-20 |

| IE00B0M62Y33 | 2008-05-28 | 2008-05-30 | 2000-06-25 | 2008-05-28 | 2008-05-30 | 2008-06-18 |

| IE00BDR08N26 | 2020-11-30 | 2020-11-30 | 2020-01-29 | 2020-11-30 | 2020-11-30 | 2021-01-31 |

The automatic fixes are not 100% accurate and a manual fix could achieve even better results. But, for the intended use for the distirbution data, which is quarterly forecasts, the fix is more than sufficient.

As long as the fixed date lies in the correct quarter, my forecasting models will perform well.

Summary

Data for distributions is not easily accessible. Either there is not programmatic access or the file format makes an extraction cumbersome. Further, the data has some errors.

Luckily, but the extraction and data errors could be fixed programmatically. I am confident to have generated a good database for further analyses, i.e. forecasting distributions.